The Story of The Tubes

Trembling Aspen | Series_02 Hey, Koganecho! | Issue_10

They were going to be beautiful. Lovely to behold, a wonder to unwrap. And lo, ye shall not see their form from among you, for they were too odd of shape, and without category or word.

I should have clued in when I asked at the Koganecho office, “How would you refer to these? Kotsuzumi? Chubu? Nimotsu?” And no one knew. The consensus was “roru pe-pa” (rolled paper). Um, okay?

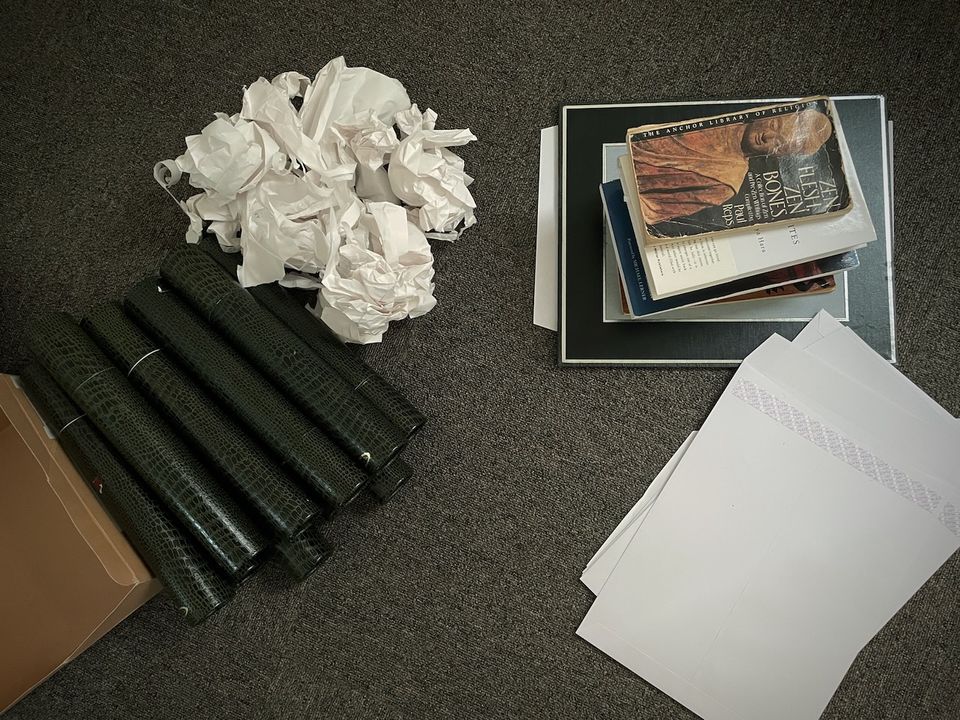

This is what they looked like, all the bokusho drawings, rolled up into lovely decorative tubes, carefully wrapped and ready to be mailed.

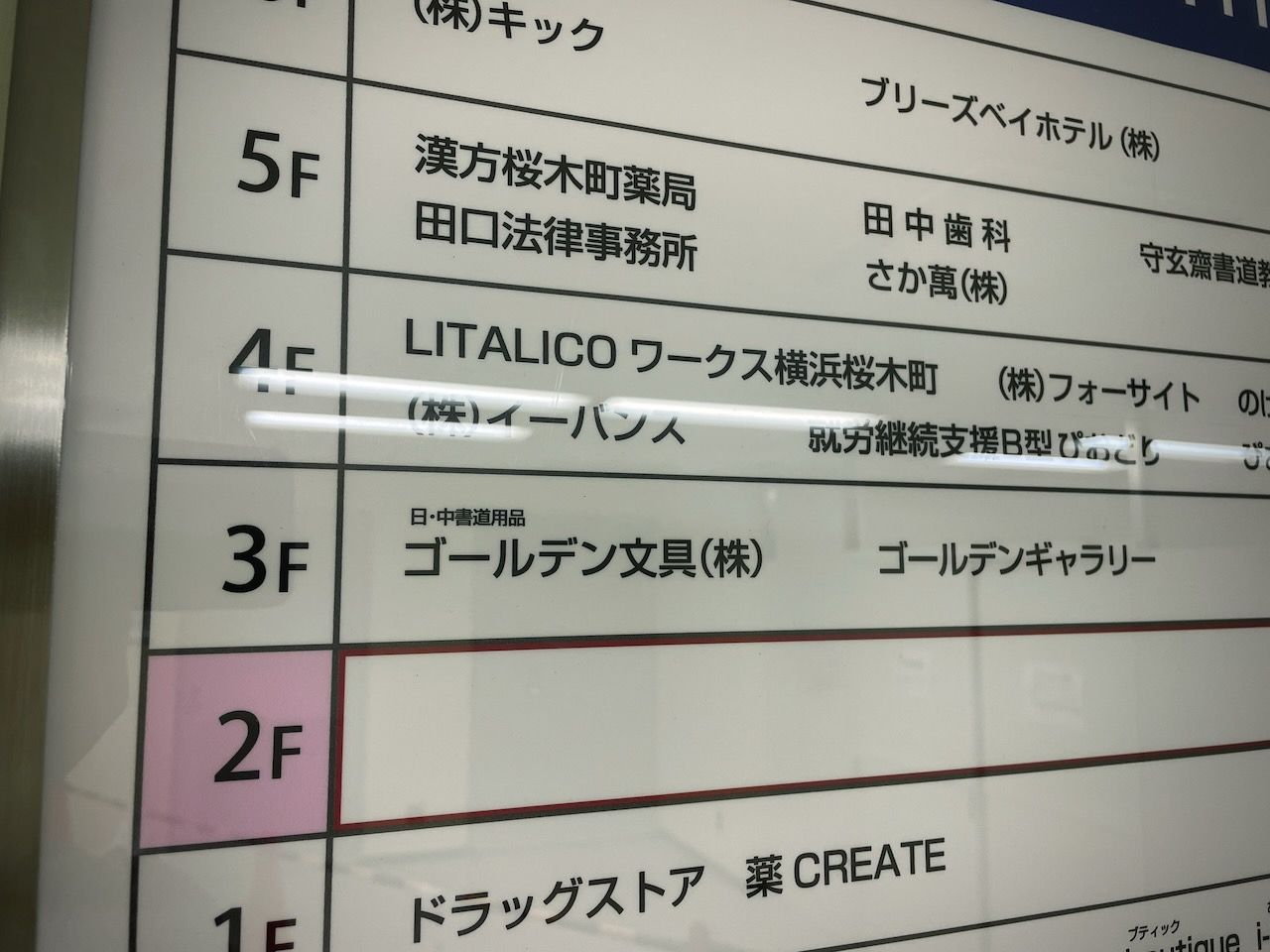

I had taken the time to have the selected work mounted (裏打ち; urauchi). Urauchi involves pasting stiffer paper to the back of the thin washi. I was glad I had it done. They look amazing. My friend Natsuki had informed me of a marvellous, near mystical urauchi machine at Golden Stationary, in Sakuragicho. It does in minutes what otherwise might take days, which was marvellous, and when I was told I could pick them up a mere 30 minutes after dropping them off, well that was near mystical.

The problem, in terms of mailing, was that a half sheet of washi* is about 2 millimeters wider than a standard A4 envelope. As I considered envelope options, I had a spine chilling vision of a postal employee folding an envelope in half. So impactful was this vision, I started looking into other options. I wasn’t going to go to Apple-un-boxing levels of fanaticism, and yet, I wanted the recipients to experience something special. I found just the thing at trusty Yurindo. Tubes. It's a rather unsexy word, utilitarian in its descriptive simplicity. Decorative tubes? They are tube shaped containers that are not aesthetically unpleasing. Just the thing. I was excited.

The bokusho art work was mounted and tube-ed. The tubes were wrapped, addressed and ready to go. This is where it gets interesting.

Is it interesting enough to sit down and write about? I told Nick the story on a zoom call, and he said it was. So, if it isn't, blame Nick. Okay, that's not fair. It's worth writing about. Here's why. As an artist, one of the ways I think about what it is I am doing at any given moment, to help me better understand what it is I am doing, is to think about studio concerns and gallery concerns. Studio concerns have to do with actually making art. It might involve a literal studio, and it may not. It's a metaphorical studio concern. Gallery concerns have to do with making art accessible. It may involve an actual gallery, and increasingly these days, it does not. Again, it is a metaphorical gallery. I use the word access in its deepest, richest sense. Accessibility.

If I'm ambling down the street in jeans and t-shirt, and happen to walk by an expensive French restaurant, it is technically accessible to me, but is it accessible in a practical sense? I might have socioeconomic barriers to entry. I might be in a wheel chair and can't physically get in. I might have a baby in my arms and can't operate that particular kind of door handle. Additionally, there might be a whole bunch of cultural and internal narratives telling me I don't belong, I shouldn't go in.

That sense of "I don't belong in there," if you've experienced it, is often how people feel about literal art galleries, and/or the art world in general. Art gets made, and is it accessible?

On the one hand, when the restaurant surrounded by barbed wire fails, no one should be surprised, least of all the chef, no matter how good they are. On the other hand, to what extent are chefs and artists responsible for accessibility to what they offer?

It's a good question, that I answer, at least in part, by cleverly skirting around it. (Or maybe it just dissolves?) If I am living my life like a work of art, then gallery concerns and studio concerns are studio concerns. How might I approach making my art accessible in the same way I approach making art?

For me, it meant genuinely enjoying the acquisition, wrapping, and labelling of the tubes. I reminded myself that making my work accessible is part of the work, and then I could settle into enjoying it. Likewise, this story of the tubes, as a gallery story, was no less important for being so. It's about making something I made for you, accessible to you.

Without further ado, let me introduce you to Kaneko-san.

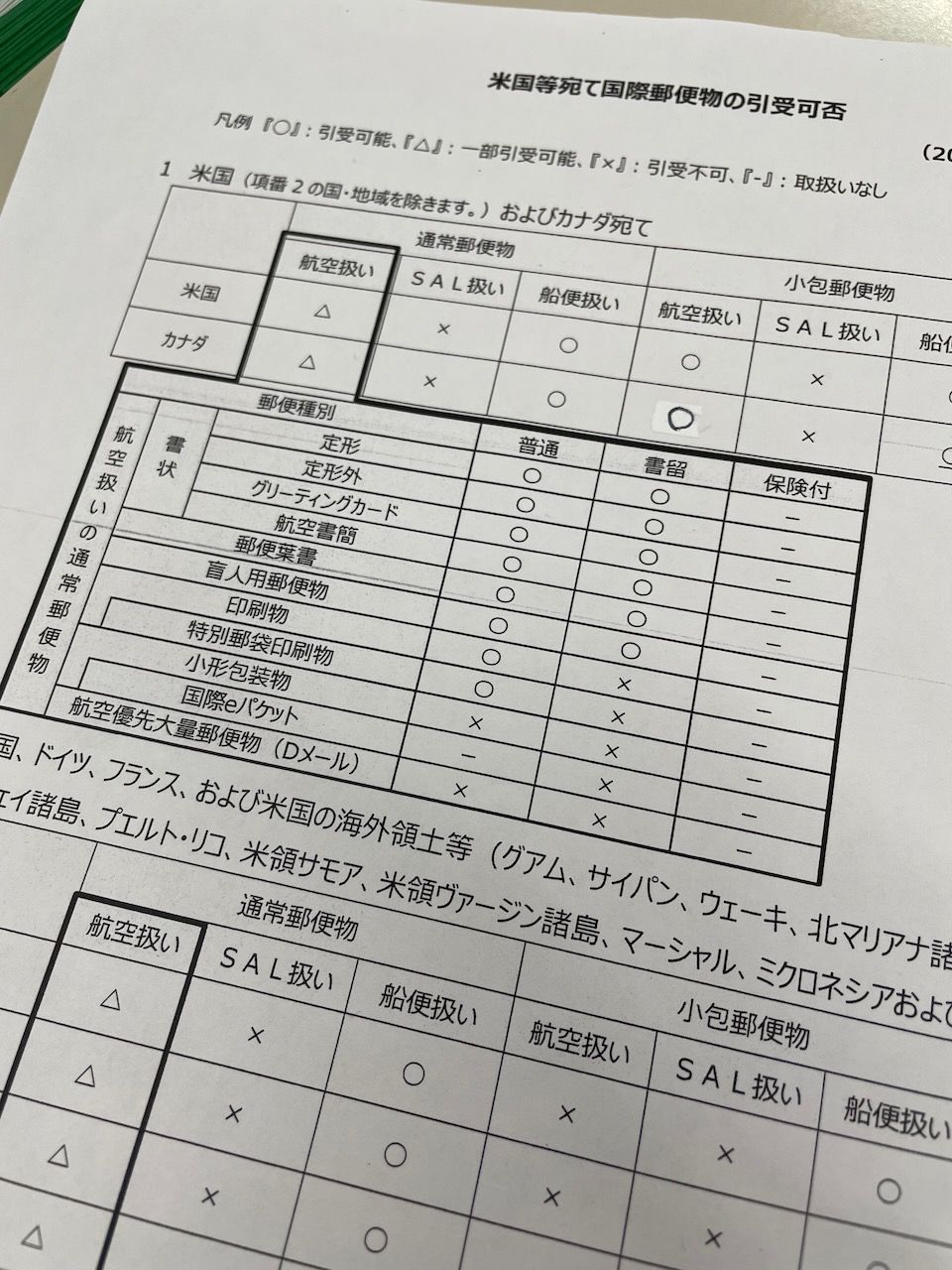

Kaneko-san is the eternally patient, effortlessly helpful post office employee who helped me mail the bokusho art work to those of you who are to receive them (have already received them?). Boy, did I luck out. Or maybe all postal employees in Japan are this helpful. I suspect it is so. The following picture is but a sampling of what Kaneko-san and I were up against.

And I say we, because he was in this with me, trying to figure out what these tubes might be called, in which box, on the above impenetrable page, might they belong, and was there a circle (acceptable), a triangle (partially acceptable), an x (not acceptable), or a dash (not handled) in said box. "What is the difference between not acceptable and not handled?" you ask. Perhaps the only person who knows sits in a basement somewhere, drafting these documents under the pale glow of blinking florescent lights, a low evil cackle leaving their lips just before a cigarette and its attendant curl of smoke arrives at the same location. Kaneko-san didn't know, for sure neither did I.

From our very first exchange, "Are you sending them all together or separately?" "Separately" his wincing response, "Oh! That's going to be difficult" all the way to his final words as I headed out the door almost 40 minutes later, "I'm sorry we didn't solve it completely satisfactorily, and I'm glad to have the opportunity to help" Kaneko-san was the embodiment of Japanese helpfulness. Really, truly happy to be doing his job and to be of service. Either that, or he was a very good actor. When I asked him where he wanted to be photographed he chose the spot in front of the post office bulletin board, the proudest possible place he could be.

Alas, the solution was not completely satisfactory. In the end my only option, given the vagaries of international postal regulations and barring a 4 month journey by boat, was a simple envelope. As it turns out the urauchi process shrunk the pages ever so slightly, and they now fit (barely!) into a standard A4 envelope, so that's how they've been sent. Those of you receiving them should see them at your doorstep in the next few days, thanks to the wonders of air travel.

All is well that ends well.

In a previous Issue I wrote about being local. A language barrier was definitely part of the story of the tubes. Kaneko-san had a small translation gadget into which he would speak, and out of which came an English translation. It didn't work perfectly, and in some ways made the language barrier more present, more visible. At one point it translated the Japanese word for paper (kami) as God (also kami). "You have to send God in an envelope." We had a good chuckle over the poor little device that had no context and therefore didn't know any better.

Being local means speaking local. I’ve been pulling up my Japanese language study socks lately. This little stage play, me and Kaneko-san in the 郵便局 (yubinkyoku, post office) is good reminder as to why acquiring a language is worth the work. Local is a place, and mostly it's people. I’d like to return to the post office someday, and speak comfortably to Kaneko-san, and have another chuckle over sending God in an envelope.

* washi means paper. So saying washi paper is like saying paper paper, and I just can’t bring myself to do it. Also, for future reference, sumi means ink. So saying sumi ink is like saying ink ink. Same thing, I just can’t do it.