What is local?

"The aesthetic of a Japanese garden has been transplanted here, but you won't find a garden like this in Japan, because it reflects southern Alberta. The rocks in a Japanese garden are almost like the bone structure of a human being. It is an essential part, different shapes, different forms, different connections…[These] rocks are Canadian rocks, the rocks are Alberta rocks."

~ David Tanaka and Tosh Kanashiro speaking about master gardener Roy Tomomichi Sumi and the legacy of his design principles on Nikka Yuko Japanese Garden in Lethbridge.

Roy Sumi was pivotal in the design of Nitobe Memborial Gardens on the campus of UBC here in Vancouver. He viewed a Japanese garden in Canada as a garden that has been created with “local materials in a Japanese style.” When I’ve mentioned this approach to my born-in-one-place-living-in-another-place friends[1], the response has universally been, “Oh, I like that!”

For instance, my friends from Japan now living in Canada can think about how they are creating art with local materials in a Japanese style. Being born and raised in Japan, they are automatically conduits of a Japanese sensibility and style. Further, and this is the part they get excited about, what’s true of their artwork is also true of the life they are creating here in Canada. They are creating a life-in-the-Japanese-style with the material of local-experiences-and-memories-with-local-people-and-things.

This approach, it seems to me, is a wonderful way to do an artist residency. I’ll be using local materials, including the material of experiences-and-memories-with-local-people-and-things, in a Canadian style.

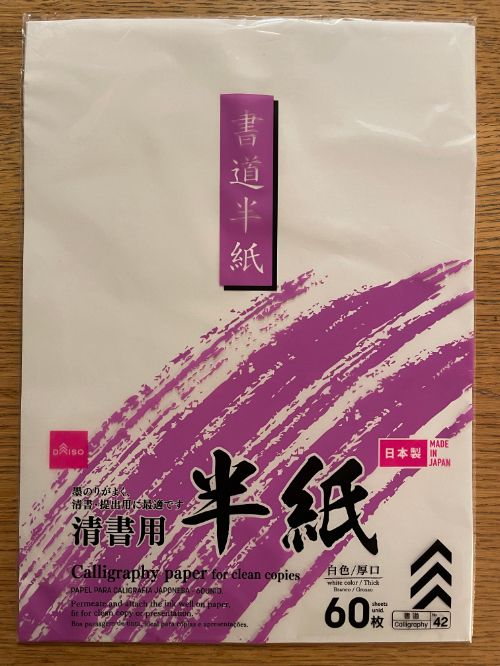

For example, I will find an art supply shop in Koganecho, head there, buy paper, and bring it back to my studio. I could go down to Daiso here in Vancouver, buy the exact same kind of calligraphy paper imported from Japan, and bring that with me to Koganecho. And that made-in-Japan-obtained-in-Vancouver-brought-back-to-Japan material would be totally different material for me to work with.

I was doing bokusho work about a month ago, hoping to get through some fruitful experiments so that when I arrive I hit the bokusho ground running. It wasn’t clicking. I was struggling. I decided on the above approach, to use local material, which includes my experiences of obtaining said local material. It is, perhaps, the opposite of hitting the ground running. I’m acknowledging I can’t start walking, let alone running, until I hit the ground. Until I am local.

No bokusho until I get there.

As to the art making I have been doing, I’ll tell you about that next issue.

Pico Eyer uses the much more poetic and elegant term The Great Floating Tribe to describe folks, including himself, who are born in one place and now live in another. If The Great Floating Tribe were a nation, it would be the fastest growing nation on earth, and its population would be nearly the size of the United States of America. ↩︎

If Nitobe Garden is a Japanese garden in Canada, what would a Canadian garden in Japan look like?

This is a salient question, as I metaphorically refer to any project I am currently tending to as “a garden.” I like the idea that because I am Canadian, I am automatically a conduit of a Canadian sensibility and style. Is it distinctly Canadian? That I don’t know. And who can say what distinctly Canadian means anyway? On the one hand, according to European history, we are an exceedingly young country, especially compared to Japan. On the other hand, indigenous folks have been tending to the land we now call Canada for over 10,000 years.

If I thought my projects needed to be distinctly Canadian—the way Japanese gardens in Canada are distinctly Japanese—I don't think I'd be up to the task. However, taking the approach that I am Canadian, therefore my projects are automatically in a Canadian style, well, that I can live with.

These are my thoughts with little more than a week to go before departure.

A documentary about Roy Tomomichi Sumi, the master gardener who played a pivotal role in designing UBC’s Nitobe Gardens, and the complex story of Japanese gardening in Canada.

A brief article about the documentary.

A Canadian Encyclopedia (who knew?!) entry about Japanese Gardens in Canada.

———

A documentary about Roy Tomomichi Sumi the master gardener who played a pivotal role in designing UBC’s Nitobe Gardens, and the complex story of Japanese gardening in Canda. https://gem.cbc.ca/media/absolutely-canadian/s20e33

An brief article about the documentary https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/absolutely-canadian-borrowed-from-nature-roy-tomomichi-sumi-japanese-gardening-1.5801058

A Canadian Encyclopedia (who knew?!) entry about Japanese Gardens in Canada: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/japanese-gardens-in-canada

*Pico Eyer uses the much more poetic and elegant term The Great Floating Tribe, to describe folks, including himself, who are born in one place and now live in another. If The Great Floating Tribe were a nation, it would be the fastest growing nation on earth, and its population would be nearly the size of the United States of America.