The Gift

Trembling Aspen | Series 04_My Life Here | Issue_12

Yamazaki-san has just finished explaining how to get on the paddle board. I’m following the Japanese only explanation pretty well, mostly because he’s doing the thing he’s talking about, so I’m seeing it while hearing it. Gaeun is translating the Japanese to Korean for the visiting Korean artists, absolutely none of which I understand.

I kneel down on the dock, as instructed. The paddle board is in the water, right beside me. I am positioned exactly how I will be in a few moments once I’m on the board. Despite it being called stand up paddle boarding, one begins on one’s knees—in supplication to the gods of gravity I imagine. I knee-step sideways, carefully placing one knee on the board. Then, before discovering the extent of my hip flexibility, I gingerly place the other knee on the board so as to be in the very-precisely-marked-centre of the board. I very precisely position my body in as exactly the centre as I can. I’m not so much thinking about doing this as instinctively following my body’s wisdom in knowing what to do, because my body, it turns out, really doesn’t want to fall into the river. I don’t fall in the river. So far so good.

I paddle around on my knees for a bit, getting used to being on the water, feeling rather nostalgic for childhood summers spent paddling around the Wye Marsh, my Dad teaching me how to properly dip the paddle into the water and then finish with a “J stroke” so you can paddle on one side without going around in circles.

A group of artists from Space Ppong in Gwangju, Korea are in town for a talk event celebrating 10 years of residency exchanges between Koganecho and Space Ppong. The event was last night, and as we chatted and mingled I discovered three of the artists were going SUP boarding today. I got invited/tagged along.

//

I decided to tag along mostly to experience being on the river. My relationship with the river has been slowly changing since I started the Flow Project. That project, you may recall, is helping people imagine a hopeful future. Imagination, I am convinced, is the first tiny but important step toward creating a hopeful future. In this instance, Flow is helping people imaginatively feel care for the river—or ecological empathy as it’s known. The project, you may also recall, is a tiny little step toward prototyping a viable multivalent currency that is part of a bio-regional banking system (woah, that escalated quickly).

<aside>

If you don’t know what multivalent currency or bio-regional banking means, well, join almost everyone else on the planet in that regard. It is a completely new and regenerative way of thinking about money and economies. It connects monetary value to ecological health. Basically the exact opposite of what we have now. Maybe the only salient thing to know is, this stuff is on the leading edge of a radically re-imagined hopeful and inclusive future. (Yes! Realistic, pragmatic and hopeful people still exist!) If you are nerdy enough to be interested in regenerative currencies and economies, you can read a presentation-in-progress about the beginnings of an actual, tangible prototype happening in Montreal called Bio-regional Currency for Air Quality.

</aside>

Anyway, the Flow Project asks If the Ooka River was a person, what would it want? Visitors to the exhibition have been offering their imagined answers. There are now just over 160 messages of wildly varying sentiments taped on the wall.

In conjunction with the Flow project is a video piece called Two Minutes of Video From the Middle Of All the Bridges Between Yokohama City Hall And KocoGarden Facing West. (a.k.a. All the Bridges) The title is the explanation. Enough said.

The audio track of All The Bridges is my poet friend, Soramaru Takayama, reading all of the messages left by visitors. It is, as the curatorial statement says: “The Voice of the Ooka River as imagined by participants of Koganecho Bazaar 2024. Performed by poet Soramaru Takayama.” The video piece is quite soothing. Salarymen have been known to fall asleep listening to the voice of the Ooka River. (Sadly, no photographs exist, but this did actually happen)

Visitors have given the Ooka River a voice, and Sora is bringing the voice alive. In response, I will take some time to listen to what the Ooka River is speaking. I will then, through some form of artistic expression yet to be determined, speak back. By speaking and listening, the Ooka River and I—in collaboration with visitors to the exhibition—will have started a conversation.

//

Paddling down the Ooka River on a SUP board, I note, I’m much less in my head and much more in my body. Rather than think about it, like an objectively interesting topic or problem with which to engage my intellect and energy, I am feeling the violation of the debris, garbage and lack of care I see. Yamazaki-san, I notice, is deftly scooping plastic bags out of the river with his paddle, piling them on his board to dispose of later. It's a quiet act of care in contrast to the let's-throw-this-shit-in-the-river attitude that got the plastic bag there in the first place. I’m writing Solarpunk fiction about the river these days, so I decide to write a scene about Yamazaki-san's quiet act of care.

//

Okay, so...Solarpunk fiction and why I'm writing it will take some explaining.

“Solarpunk is a literary and artistic movement that envisions and works toward actualizing a sustainable future interconnected with nature and community. The "solar" represents solar energy as a renewable energy source and an optimistic vision of the future...while the "punk" refers to the countercultural, post-capitalist, and decolonial enthusiasm for creating such a future.” ~ Wikipedia

Whereas Cyberpunk imagines a future in which we’ve gotten everything wrong, Solarpunk imagines a future in which we’ve got things right. At one time a niche sub-genre within speculative science fiction, Solarpunk is being increasingly noted for it’s capacity to evoke environmental empathy and engender hopeful imagination for a better, more equitable, regenerative and absolutely possible future.

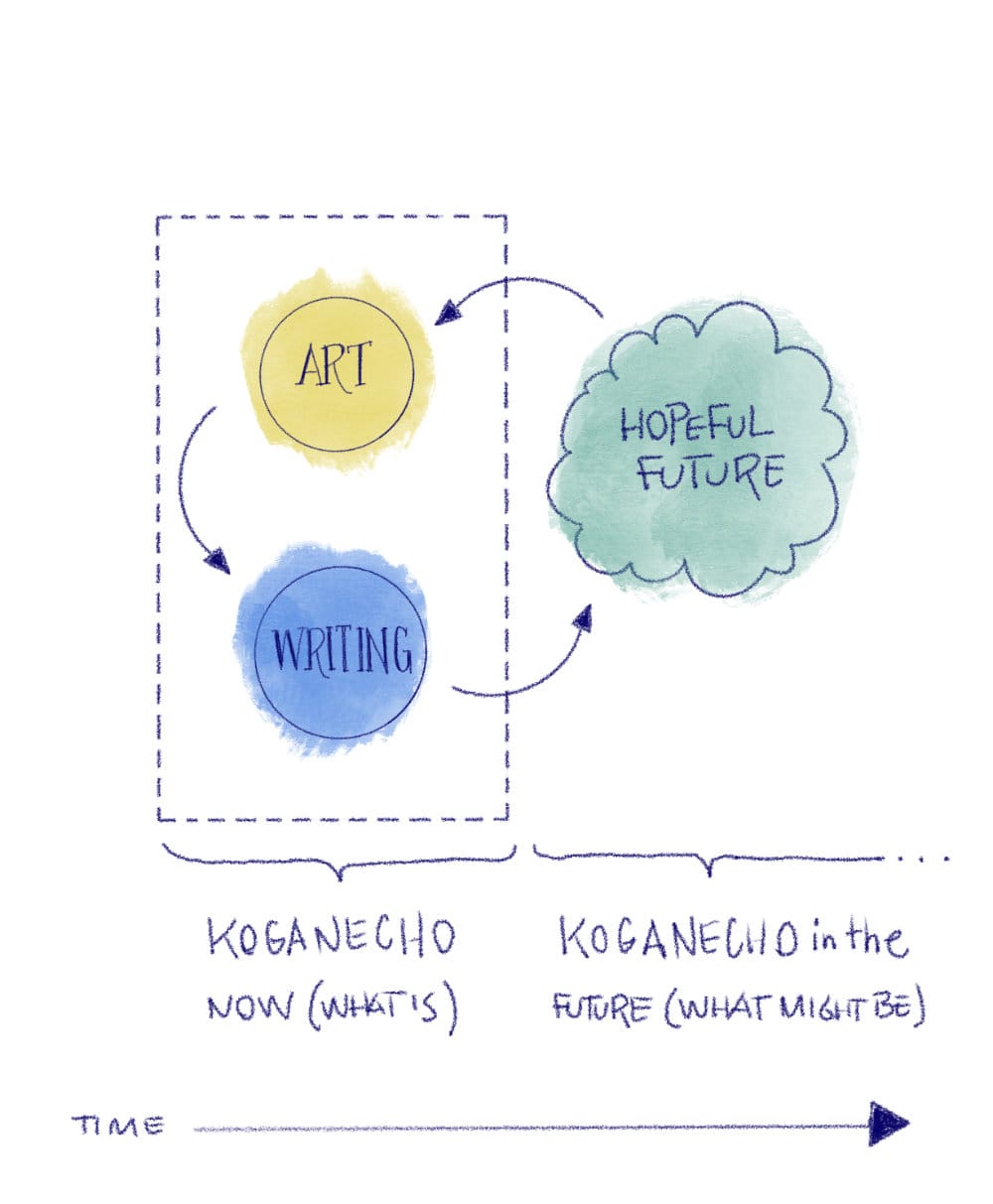

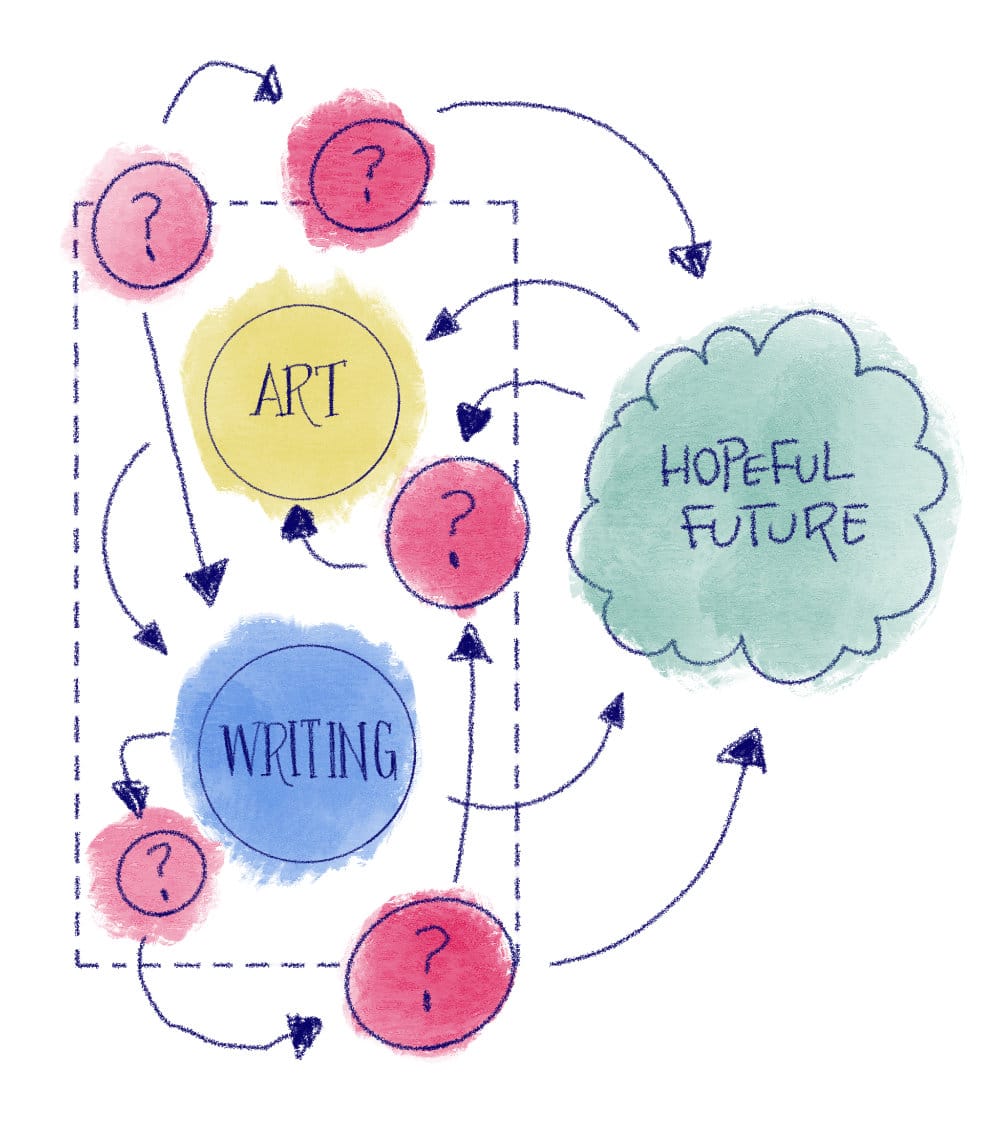

I’ve come to realize, helping people imagine a hopeful future is what KocoGarden is about. It’s what KocoGarden is about because it’s what I’m about. It nice, arriving at simplicity that was there all along.

I am now doing two things out of KocoGarden:

- In the real-world neighbourhood of Koganecho, I am collaboratively creating art installations that give people an experience of a hopeful and regenerative future.

- At the same time I writing Solarpunk fiction about a hopeful and regenerative future set in an imaginary Koganecho-of-the-future.

The two dynamically inform each other. It’s exciting and fun. My stories and art-making can be just the beginning. Like kombucha mushroom, or sourdough starter, they just serve to get the imagination fermentation going. People can write their own stories, artists can make their own installations. Who knows what else will get invented when the creativity starts brewing.

The creative process started with my body living and moving and breathing in Koganecho. The writing started with an image in my imagination. For my own purposes, I described this scene by way of a poem. I now think of the poem as a sourdough starter, or a kombucha mushroom, it's a place to start and gives continuity to all that will come. Thus, I’ve titled it “The Mushroom Poem”

Looking to the sky

in expectation

agile and lithe of body

fluid and open of mind

a figure stops

on Asahi bridge at midspan

White-on-blue clouds

host the approaching gift

The Mushroom Poem is allowing me to write little scenes set in the future-world of Koganecho. It. Is. So. Much. Fun! Anything I like can become part of this world. Better yet, anything I encounter in and around Koganecho, that I like, can become part of this world.

The even more fun part will be creating ways for others to participate in the co-creation of this imaginary future-Koganecho. What is the gift?! I don't know yet! But, let’s leave all that for the next issue. In the meantime, here are a couple of little scenes I've written.

Bridge Scene

Looking to the sky

in expectation

agile and lithe of body

fluid and open of mind

a figure stops

on Asahi bridge at midspan

White-on-blue clouds

host the approaching gift

Rain on the way. The Ooka-Kami will be restless. Aki didn’t like it when the Kami were restless, it meant he’d have to walk to the Song Station more often, not less. Which meant following his father more than once today, which was bad enough in itself. The rain would make it worse.

The 7:09 headed to Zushi-Hayama made it’s quiet but hurried way past. He loved that sound. It meant things were as they should be. The Keikyu main line, ran right down the center of the neighbourhood, like a backbone but with Regen-trains running up and down it. Hinodecho Station at the head, Koganecho Station at the feet. Hiromi said it was the other way around, Koganecho Station was the head, but that would put the head at the south end, which to Aki made no sense. Besides the Ooka River ran north, to Tokyo Bay. Well, technically it ran both ways, because it was tidal water, as Hiromi had pointed out. She could be so stubborn about the stupidest things…and why was he wasting time thinking about it when she wasn’t even here?

He looked up at the clouds one more time, waved to Mr and Mrs Hayashi, over on the east bank, shuffling their way to the co-op. They were as old as dust, and still moving. He loved them. Then with a hop and skip, he darted the opposite direction, toward the tracks. Better get home before the rain starts. Better to get off the bridge before the harvesters saw him.

River Scene

Aki’s swift was made by his grandfather, so it has his grandfather’s secret design. Which means it’s faster than Hiromi’s swift. When Aki starts paddling, he goes into an almost trance like state. On the water is where he feels most free, most like himself. When he gets in his paddle-trance, he forgets Hiromi is with him, and that her swift isn’t as fast. "Hey! Squid-brain!" she shouted after him. He barely heard her, she was so far behind. He stopped paddling, a bit frustrated that he got bumped out of his trance, and a bit ashamed he had left his friend behind. She could run faster than him, and she always made sure not to leave him behind. “Keep up, ne.” She would say, teasing him, making fun so he didn’t feel so bad about it.

The paddle made a little wake in the water as he drifted, waiting for Hiromi. He lifted the tip out of the water. He fell into another trance, staring at the little drips of water that fell into OokaGawa-sama. Did she feel these little drops as they fell back to her body, he wondered. Did it feel good? He was sure his swift gliding over her was something she enjoyed. Every day he asked OokaGawa-sama permission to put his swift on her surface, and every day she said yes. That’s how he knew. And he wasn’t just anyone asking. He was a River Steward. Third generation, after OokaGawa-sama’s Kami was officially recognized by the Office of Dark Matter. That had been a long time ago. Old people, of old people, of old people. He was happy to light incense to his ancestors, but he wanted to be a River Steward his own way. He understood OokaGawa-sama in a way no one else did. He knew it in his bones. Every day he asked for permission, and every day she said yes.

//

I had a chance to visit the Wye Marsh last year. I hadn’t been back in decades. This visit gave me a new found appreciation for my Dad bringing me here. I can’t imagine I was overly enthusiastic about paddling around the Wye Marsh when the-world-of-everything-the-late-70’s-had-to-offer-the-little-town-of-Midland-Ontario including, but not limited to: Shopping-malls! McDonalds! Rollerskating! was awaiting me elsewhere.

I could see on this more recent visit, in retrospect, the gift of my Dad’s gentle nature, and how it had quietly filtered into my consciousness at the Wye Marsh, had given me a head start on my own ecological empathy.

From my journal that day at the Wye Marsh:

“From up on the observation deck, I recite, one by one, my Pacific Spirit mantra. First to the chickadee, then the Red Winged blackbird, and then to the frog in the pond down below. To each of them I say: ‘May you be at ease. May your heart be open. May you be at peace. May you be free from suffering. May you live fully, and as yourself.’ In the middle of the recitation I realize, each of these creatures already knows how to do all of these things. I have much more to learn from them than they could ever learn from me. The mantra shifted from me-sending-it to me-receiving-it, as sometimes happens with the trees.”

Thanks Dad.

Hey, I’m Steve, an artist-in-residence in Yokohama, Japan. I make collaborative art, participatory art, interactive new media installations, and abstract visual art. I explore themes of home, identity, belonging and how to live your life like a work of art. I write about it all in this very newsletter, Trembling Aspen.

I’m learning out loud so we can learn together.

If you would like to support me, my residency, my work, and this newsletter, or if you are interested in crowd-funding interdependent art-making in Yokohama, Japan, please consider subscribing.