How do you know you are home?

Trembling Aspen | Series 04_My Life Here | Issue_01

On my last day in Yokohama, Natsuko, one of the exhibition curators, stopped by KocoGarden to chat about, well, KocoGarden. Natsuko was born and raised in Japan. Koganecho is where she works. Her home is elsewhere, a brief train ride away. She asked “How do you feel about the project?” Within the wandering thread of that conversation we began to talk about home: geographic home and the idea of home, where you are from, where you are now, where you are going. We talked about how, if you are to be hospitable, you need a home to invite someone into. We talked about how KocoGarden had become a kind of bridge between cultures. It isn’t here–where I am—and it’s not there—where you are—but in-between. It had become a place that lets us both move away from the safety and comfort of here—whatever here represented for us, either an internal state of mind or a physical space, usually both—to meet in the middle. Mutually liminal space.

I had noticed, of the goings on in KocoGarden, that when people bravely moved away from their safe and comfortable here to meet with others in a middle that wasn't here nor there, what they naturally shared was stories. Stories about family, friends, neighbourhoods. Stories from a-place-once-called-home. They shared stories of a place somewhere beyond our current shared neighbourhood of Koganecho. They shared a version of home they carried with them in their hearts. Further, when there was trust and bravery, people shared a version of home that included things like hurt and disappointment and shame and pain. When there was trust and bravery, they revealed the-home-they-carried-in-their-hearts to be imperfect, perhaps insecure, and thus deeply human.

In KocoGarden, the way this transfer of stories of homes-in-our-hearts happened was through table culture. By table culture I mean the way people interact, share food and engage in conversations during meals. Table culture, in other words, is undeniably shaped by a-place-once-called-home. People shared literal food that was symbolic of, and invited people into, the home they carried in their hearts, a place once called home.

This practice of sharing stories through table culture, it seemed to me, became a way of processing and making sense of the home-in-our-hearts. A way of shaping the thing—for good or ill—that had shaped us, and a way of making sense of where we were now. Here.

Recently, I sent a message to Gaeun, who is from Korea, living in Koganecho as an artist-in-residence, and currently participating in an artist residency in China. Despite being fluent in five languages, Gaeun continues to work at more fully inhabiting the home-in-the-hearts of speakers of each of those languages. She does this by constantly adding to her store of idioms, phrases and vocabulary. Being a self avowed habitué of thesauri, I am happy to help out, as far as English goes, by sending random vocabulary building words along with an example sentence. Home came up yet again.

peregrination: A traveling from one country or place to another; a roaming or wandering about in general; travel; pilgrimage

“A peregrination isn’t so much about leaving home as it is about making one’s journey a kind of home.”

Is that possible? Can home be a journey? Perhaps "a kind of" is the important part of that sentence. On one level, in some ways, yes, home can be a journey. And yet, we humans still seem to need some kind of centre, something to tether to, somewhere, somehow.

I flew out of Haneda airport on my way back to Canada. I’ll be home in Vancouver for November before returning home to Yokohama the beginning of December. (I used the word home for two different places in once sentence. Is that permissible and/or advisable?) On my way through the Security Hoohaa (the official name for it), I experienced something I’ve never experienced before, being from one place and living in another. There was a phalanx of about 20 customs and immigration booths in front of me. About 10 were designated Visitors and 10 were designated Residents. "Which one," I wondered, shiny new resident card in hand, "do I leave by?" Well, it is a resident card, and the word resident is right there...so...? I checked with an employee, showing her said shiny new card. “Which gate do I go through?” I asked. “This way,” she said, indicating the Residents side. I am a resident? Am I a resident? How do I know I’m a resident, other than the word resident on my resident card. Why was I not sure? Why did I need to ask? What do I make of my slight discombobulation? Was this simply an example of categorical insufficiency—that is, categories are never as clear as bureaucratic institutions like to think they are—or had I just crossed a threshold of experience an landed in another home-in-my-heart?

After arriving in Vancouver, and getting adjusted to re-new-ified-and-yet-familiar surroundings, I had a call with my friend Nick who lives in Australia. After moving a lot as a kid, he’s been in his current neighbourhood in Adelaide for over 30 years. The writing above—read carefully by you no doubt—had been rattling around in my head the past few weeks and hadn’t yet been formed into a first draft. So I asked Nick, “How do you know you’re home?” He paused, in a distinctly Nick-esian way. His response, considered, not rushed. Which is one of the reasons I like talking to Nick. He takes my questions seriously, even if they’re random, like this one, and I know I’ll get an interesting answer.

All of sudden it was an hour later and I had typed a bunch of notes. The following is a mildly coherent summary of a wandering and invigorating conversation with Nick.

Home is familiar. First off, you know you’re home by way of familiarity. When you spend time in a place, you gain local knowledge. Home-as-more-than-a-building, like a neighbourhood, has local knowledge. Sometimes simple obvious things like where to get stuff you need—gas, groceries, a haircut; and where to get stuff you want—restaurants, coffee shops, and a park for walking. Sometimes less obvious things, like the sounds of these particular birds, the sound of that neighbour's lawn mower, the way the shadows of the trees fall on the sidewalk differently in January than in June. If it takes 10,000 hours to become an expert at something, maybe it takes 10,000 hours to be an expert at feeling at home in a place. Familiarity only comes from spending time in a place. You can’t hack it, it takes as long as it takes.

Home is precarious. The current housing crisis, which seems to be affecting the entire planet, brings the word precarity to mind. A precarity to one's sense of home is an imposed and perverse counter dynamic to expertise-at-being-in-a-place born of longevity. The housing crisis makes us all amateurs at feeling at home.

Home is where you return to. In order to know you are home, you have to have left and then come back to it. Leaving home involves moving out of a comfort zone. I imagine a big circle on the ground, in the middle is comfort, representing things like familiarity, a sense of safety, security, competency and agency. Out at the edges of the circle, away from home (conceptual or literal) means moving away from any or all of those things.

Home sets your rhythms. Moving to the edge and then re-centering seems to have a rhythm. Daily, weekly, monthly, yearly, chapter-of-life-ly. For example: I’m going to the store, we’re going out of town for a hike, we’re going to visit grandma, we’re going to Grenada, we’re moving to Nicaragua. Or, for example: I am going to get out of bed, I’m going to talk to 3 more people than usual this week (for introverts), I’m going to spend less on coffee this month and set it aside in savings, I’m going to have a new job by the end of the year, I’m going to do the thing that I would regret not having done if I found myself in an airplane plummeting toward earth. The de-centering/re-centering rhythm is different for different people. Some people are naturally more comfortable being more frequently at the edge, in dis-comfort. As my fellow artist-in-residence, Ariane, put it, “I'm an artist, I’m comfortable being uncomfortable.” Additionally, pushing to the edge all the time may not be the best thing. Also, not ever leaving the centre may not be the best thing. Lastly, perhaps being only ever around people who only ever push to the edge or only ever stay at the centre may not be the best thing.

Home is what you make it. It’s what you invest in. Home is where you have help to survive. To whit:

KocoGarden is a geographical manifestation of your artistic togetherness. ~ Nick

Nick said I don’t have to quote or attribute him if I ended up writing about our conversation. The quote above, I felt, deserved quotes. KocoGarden is a third space, therefore not work, and not home. But it is also a kind of home too. A place to be together with familiar folks, with whom you’ve spent time, and who give you the help you need to survive, as an artist. Artistic togetherness. I like that.

Home might not be a building. Perhaps a shift is taking place, amongst the general population of the world, particularly among those feeling the long term impact of the afore mentioned housing precarity. i.e. more and more people will never own a home. If one can’t hope to accrue wealth via property ownership, and one resigns oneself to a life of renter-ship, then naturally the building one finds oneself in holds less and less emotional and psychic significance. The outward container becomes interchangeable, and the things inside the container become the important expression of one’s unique journey on planet earth. The things inside the container might be nouns or verbs. Either objects of significance—e.g. the chair aunt Margret left me, the painting we got in Madagascar, the sweater I mended last winter; or objects and space that allow for activities of significance—e.g. a TV and space for a couch on which to watch the latest blockbuster movies, room for a kitchen table on which to host potluck dinners, a chair and books with which to sit and read.

There is an interesting parallel to the realities of digital life with which nearly everyone is familiar. The laptop I own is becoming more and more an interchangeable object to which I have very little emotional attachment. What does matter is my-familiar-life-in-my-computer, stored in the cloud. My digital life is less about the computer container it is housed in, and more about the stuff inside. I had a recent experience of this digital house-move only days before. I helped my Mom set up her new iMac. Out of the box came a brand new iMac, all generic and universal in its beguiling and sleek beauty. I got it up and running, the familiar and universal logo and chime. Once started, there on the screen sat an unfamiliar digital world, in all its beautiful and universal, yet alienating and disorienting glory. I then installed the digital backup of my-Mom’s-life-in-her-computer, and up popped her familiar desktop image (the back yard, as it turns out, of the home she and my Dad had owned and lived in, a deliciously relevant irony). All of her files were sitting right there, where they had been. Visually, functionally, emotionally familiar stuff inside a new exchangable exterior. Is this how the next generation makes sense of a future in which home ownership is virtually impossible? What happens when the-thing-you-can’t-own-and-hang-on-to loses its emotional importance? What happens when the stuff inside the exterior casing becomes the important thing? What is the important stuff that you save to the Time Machine backup of your life and take with you to your next rented exterior casing of a home?

I know someone who worked for a wealthy couple. The couple had multiple properties. So many, in fact that they needed to hire someone, a concierge of sorts, to look after the logistical details required at each property should they, on a whim, decide to visit one of them. The danger they face, it seems to me, might be the inverse of housing precarity. Precarity forces upon us a capacity to carry with us a home-in-our-hearts. What happens when you have so many homes you don't have to carry one in your heart, but neither do you have a single centre to which you might tether. Might too many external containers lead to a diffusion of any visually, functionally, emotional familiar centre? An identity precarity. What, I wondered, would be in the Time Machine backup of that couple’s life? What, if anything, did they bring with them to the interchangeable containers of their many houses?

I recently told a friend, “The good thing about not belonging anywhere is you belong everywhere.” (Which feels different, I have to say, from the problem of having too many homes.) There's an implicit journey in the statement. You have to go from feeling like you don't belong anywhere, to understanding you belong everywhere. It's a difficult, internal journey we aren't prone to voluntarily embark upon. Maybe it's the journey every human is on. And, if a journey can be home, maybe it's the home we all share. Maybe the journey home to oneself is our shared human home.

After completing a first draft of this issue, I opened my laptop the next day, to finish things off. My familiar digital life blinked into existence in front of me. My journal—an object of significance affording me an activity of significance—offered its daily prompt.

What are three things I am grateful for today?

Here is my entry:

- The story of My Life In Canada, as it was, and what it made me. The familiarity of my place, my home, my community in Vancouver.

- The new story of My Life Here, the first blank page waiting to be filled starting December. By here I mean a citizen of the world, a resident of nowhere and thus everywhere.

- The familiarity of my place, my home, my community in Koganecho. How it has re-centered me. How it is a home base from which to frequently venture to the edges of unfamiliarity, discomfort and growth.

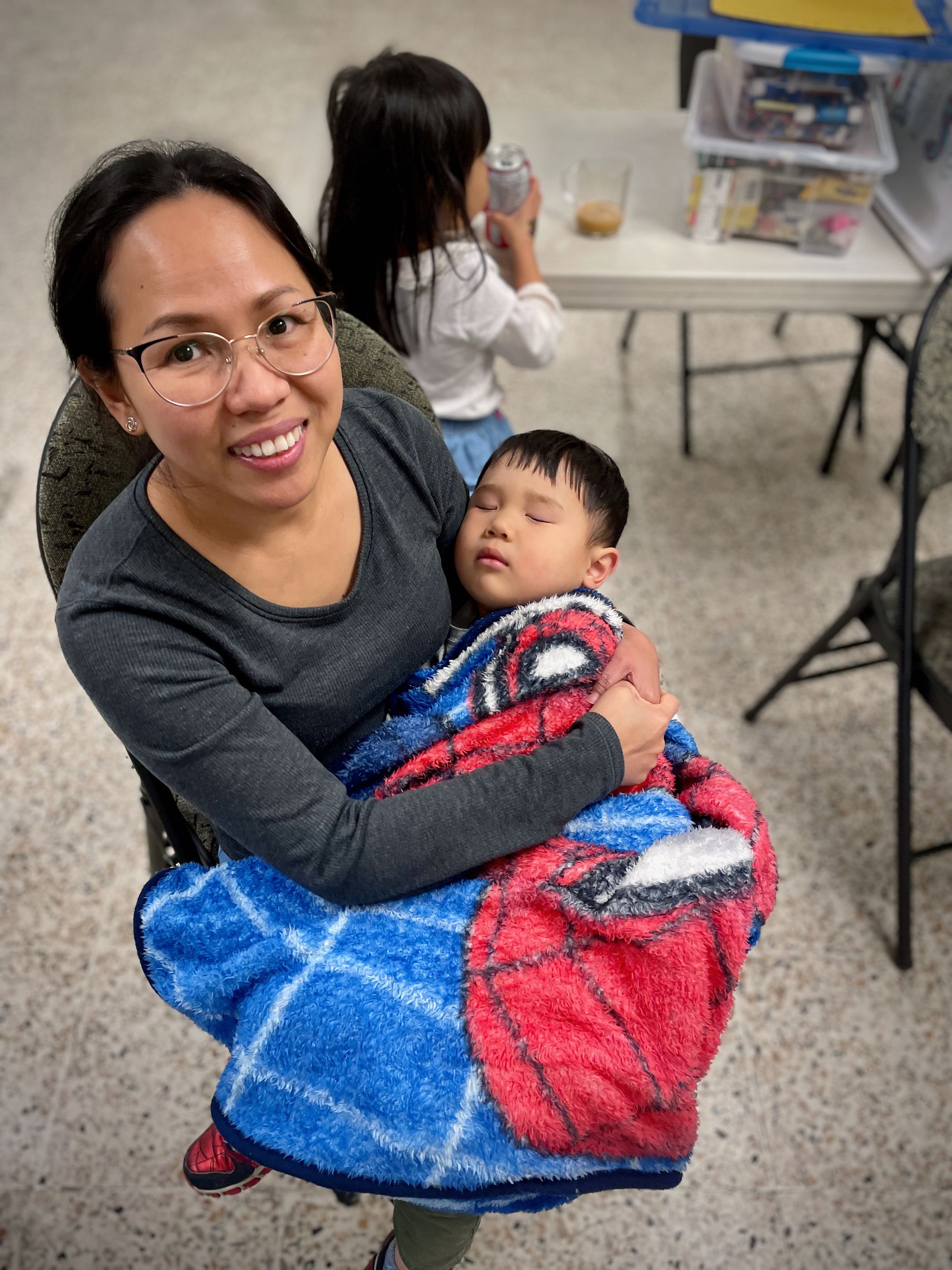

Recapitulated in photographic form, the same list not as entered in my journal, but as recently posted to Instagram, for your (re)viewing pleasure.

3.

My participation in the Koganecho Artist in Residence program, the art work I create while here, and this very newsletter were all made possible by members of The Mycelium Council. If you enjoy Trembling Aspen, a newsletter about living your life like a work of art, from me, Steve Frost, please consider joining.