Drifting toward a world we all want.

Time, money, space. (時間、お金、場所)These, according to curator WAXOGAWA (Rakuki Ogawa | 小川楽生), are the main concerns of artists in Tokyo. “There are lots of small art communities in Tokyo, and it’s difficult to connect them. Connecting grassroots with a market, upstream / downstream, is also difficult.”

I’m chatting with WAXOGAWA in the basement of The Yokohama Civic Gallery in Miyazakicho, a stone’s throw from Koganecho where my artist residency is based. I was here with Yuri, another Koganecho AIR artist, just yesterday. Yuri and I accidentally went to the other Yokohama Civic Gallery in Azaminocho before realizing our mistake and making our way to Miyazakicho, which I mention only because having so many civic art galleries that you get confused as to which one you are headed is maybe not such a bad problem to have.

And yet, despite an apparent abundance of civic galleries, we have that pernicious list mentioned off the top. The point being, I would suggest, that sustainable access to all three—time, money and space—is the important thing. Gallery space isn’t much use if you don’t have the time and money to make use of it. It’s less of an individual artist issue and more of an art ecosystem issue.

I first met WAXOGAWA, along with co-curator Seibun (Lijingwen | 李静文), on that first visit. I was so inspired by these young curators, I went back today to chat some more. Their being young is irrelevant, save for the fact that the level of commitment and excellence they have maintained at such an early stage in their career is notable*. Any independent curator who chooses the freedom afforded by non-affiliation with a major museum or institution must also deal with the financial precarity of such a choice. To have done so, and maintained the level of excellence they have, at such an early stage in their career is what is notable. More than notable, it’s commendable, and worth spreading the word about.

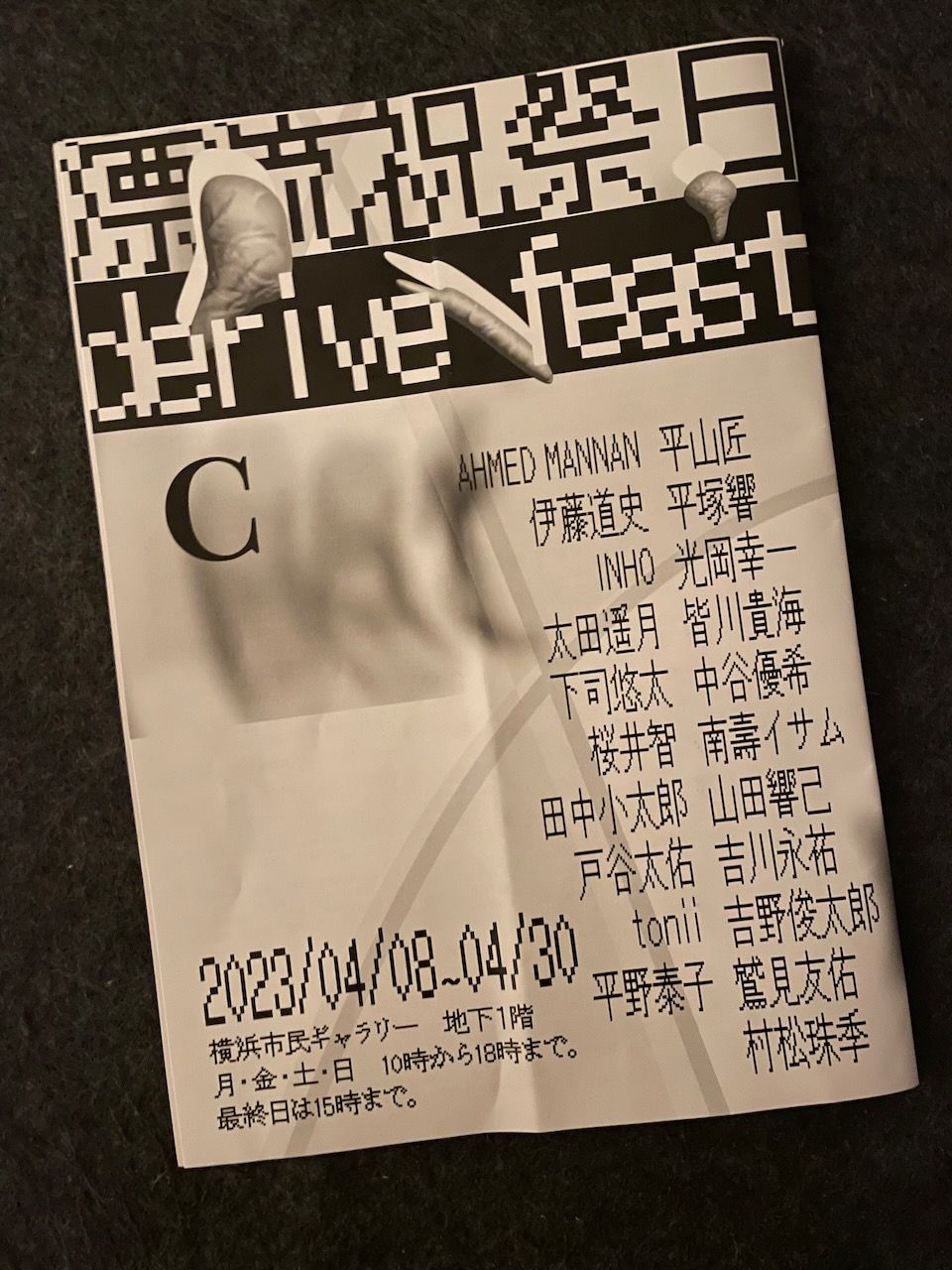

The group exhibition, which includes 21 artists all on the fringes of the Tokyo art scene, is called 漂流祝祭日, loosely translated as Drifting Holidays. Drifting, as in drifting away from, or being adrift, which can be negative or positive, depending on the level of agency associated with the drifting being done. I asked the co-curators, why are Tokyo artists showing in Yokohama? In brief, because this is where they are able to. The location is apropos of the exhibition title. In order to bravely and honestly share Tokyo as they see it, moving outside of Tokyo and the Tokyo art scene—where, WAXOGAWA points out, “art and money are tightly linked”—was both a necessity and a poetic metaphor for their collective place in the Tokyo art scene—i.e. outside of it.

The overall concept and flow of the exhibition—comprised of three rooms 身体について (about the body), 歩行について (about walking), 休息 (about rest)—was inspired by Hemingway’s “A Moveable Feast,” a memoir of his time in Paris in the 1920s. “The first room is bright colours, a kind of festival atmosphere. Of course we enjoy participating in the fun parts of our city, the restaurants and clubs and festivals. And in the background are darker themes.” That. Is. An. Understatement. The first room, undeniably colourful, includes the work of AHMED MANNAN, which makes reference to cannibalism. So, yes, dark indeed. “The second room” Seibun continues, “is about the streets, how we [artists] honestly see our city from the street level, as we live our lives.” This explanation led us off into a conversation about “grassroots” (草の根**) the importance of grassroots networks and their perspective, and the importance of art’s capacity to invite questions. Thus, the importance of this exhibition, in that it is inviting questions from below, rather than giving directions from above.

This second street level room included a VR installation by Michifumi Itō (伊藤道史). The VR goggles, if you’ve not encountered them, make the wearer blind to an unmediated world, and dependent on a virtual representation of the world. The viewer, in this case me, navigates a short walk which includes stepping up onto, and subsequently off of, four curbs about 4cm high. At one of these curbs I had to pass through a wall of prohibitive street signs—stop, do-not-enter, etc.. I knew, in my conscious mind, the signs were only virtual and not real. And yet my body hesitated more than once before I could muster the mental and physical coordination needed to step off of the curb. It was a direct experiential encounter with how literal signs guide our behaviour in ways we aren’t necessarily conscious of. The artist is interested in feet as the interface between the real world and VR worlds. They draw attention to the paths (literal and metaphoric) we must navigate everyday in our respective cities, and how our journeys possess an inherent tension between the real world and a world of unspoken messages.

“The third room,” Seibun explained “is about moving inside, to one’s thoughts. Almost like meditation.” This is where I discovered the work of photographer Takaumi Minagawa (皆川貴海). “As a photographer” he explained, “I’m interested in removing myself (my ego) from the act of clicking, of taking a photograph.” His process, for this particular series, was to ride a night bus, and while doing so to hold unexposed photographic paper up to the window of the bus. “The lights passing by the bus directly exposed the photographic paper, I wasn’t involved in deciding when to take the picture.”

Lastly, I had a chance to chat with Geshi Yūta (下司悠太). His artistic practice is to reimagine his life, and live it. Mostly in a simple way—learning to cook simple meals like rice and miso, mending and reusing his clothes. When he participates in an exhibition, he presents an activity from the art of his everyday life, and then he has conversations with people about what he is doing. The conversations are another form of art, created right there in the gallery.

I felt, of course, an immediate sense of camaraderie. (Hopefully you do too, given that the overarching theme of these newsletters is living one’s life like a work of art.) At this exhibition he was mending socks. We chatted a bit (limited by my Japanese). I told him that watching him gave me a good feeling (いい感じ) because it reminded me of my Mom and the Enso Quilt we made together. I showed him pictures of the quilt. He liked “mu” (the kanji character in the centre of the quilt) and said sewing is like meditation. Yes, yes it is.

While we work toward a world in which there exists ample time, money, and space for everyone—as daunting and far off as that may seem—I choose to believe a couple of audacious things. While audacious, they aren’t unbelievable, just unprovable, which doesn’t stop me from choosing to believe them. First, that we are actually working toward a world in which there exists ample time, money and space for everyone. And second, these young artists and curators aren’t alone. There are artists and art allies in cities all over the world who are committed to art and to the cities in which they live. They are operating at a high level of commitment and excellence, with a firm belief in the power of art to affect positive change in the world. This thought alone, despite whatever else is going on, helps me sleep tonight.

*If I told you they were still students at Keio University, would you think less of them? Perhaps, and it would be a mistake. It only adds to my admiration for the workload they carry as a result of their belief in the power of art to affect positive change.

**草のね; kusa-no-ne; literally the roots of grass. Which isn’t really a phrase in Japanese, but we’re going to try and make it so.